Met Office

|

|

Met Office research could enhance long range forecasting skill

New research has revealed that the impact of one of the world’s most influential global climate patterns, is much more far reaching than originally thought.

Scientists at the Met Office have discovered that, away from the tropics, the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) can influence Atlantic weather patterns a full year on from the original event.

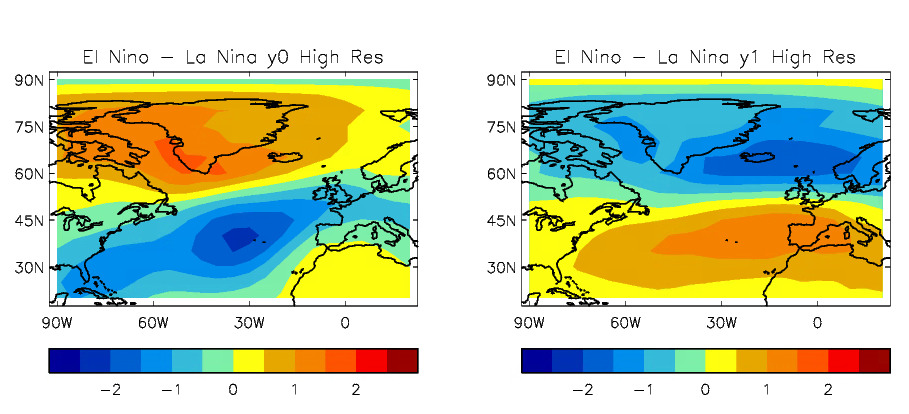

Research shows this one year lagged extratropical response to ENSO is as strong as the simultaneous response, but with an opposite impact. For example, it has now been shown El Niño, which can increase the chance of colder winters here in the UK, can result in a milder winter period the following year. While ENSO is just one of many drivers that influence the UK weather, it can be important, particularly in the winter months.

Lead researcher, Met Office’s Professor Adam Scaife, said:

“This latest research reveals that El Niño is often followed by positive North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) a whole year later, while La Niña is followed by negative NAO one year later. This has major implications for understanding ENSO, explaining our winter climate variability and interpreting long range predictions.”

Effects on Atlantic winter weather patterns during (left) and one year after (right) El Nino-Southern Oscillation events in the tropical Pacific. See level pressure changes (hPa) are plotted for El Nino minus La Nina cases from a high resolution climate model. After Scaife et al 2024.

Director of the Met Office Hadley Centre, Professor Rowan Sutton, said: “This is exciting new research which reveals unexpected potential for valuable forecasts of UK and European winter weather over a year ahead. Such forecasts could be valuable for long-range risk and contingency planning, for example in the energy sector or in flood preparedness”.

The research shows that knowledge of the previous winter ENSO event is also important for understanding some of our extreme winters. In cases in which El Niño is followed by La Niña, or vice versa, the lagged effects can boost expected impacts. For example, La Nina was followed by El Nino in 1968/69, 1976/77, 2009/10, boosting the resulting cold weather, while we saw mild and stormy weather in the winters of 1988/89, 1998/99, 2007/8 when El Nino was followed by La Nina.

ENSO shifts back and forth irregularly every two to seven years, bringing predictable shifts in ocean surface temperature and disrupting wind, rainfall and global temperature patterns across the tropics. With increased understanding of the teleconnections and impacts of ENSO, we will be better able to plan for variations in our winter weather patterns.

Link to paper https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adk4671

Original article link: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/about-us/news-and-media/media-centre/weather-and-climate-news/2024/enso-lagged-response